It has been six years since a multi-year farm bill was passed by Congress, and a new farm bill is sorely overdue.

What is the farm bill, and why does it matter for hunger relief?

The farm bill is meant to set national agriculture and food policy for five-year periods in order to support the nation’s farmers, ranchers, and food-security programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), which helps supply food banks around the country. The last farm bill was passed in 2018, with a 2023 expiration date. Negotiations for a new bill stalled in Congress last year, ending with lawmakers agreeing to a one-year extension that ends September 30, 2024.

Why does it matter if a new five-year bill is passed versus another one-year extension?

The world of 2025 is nothing like the world of 2018. Since the 2018 farm bill was signed into law, there have been huge gaps in the farm safety net due to such events as the trade war with China, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, COVID-19 and related supply chain challenges, rising foreign subsidies, inflation, and more. Additionally, the USDA-projected market prices for the 2024 crop are well below costs of production, and current projections paint another bleak picture for 2025.

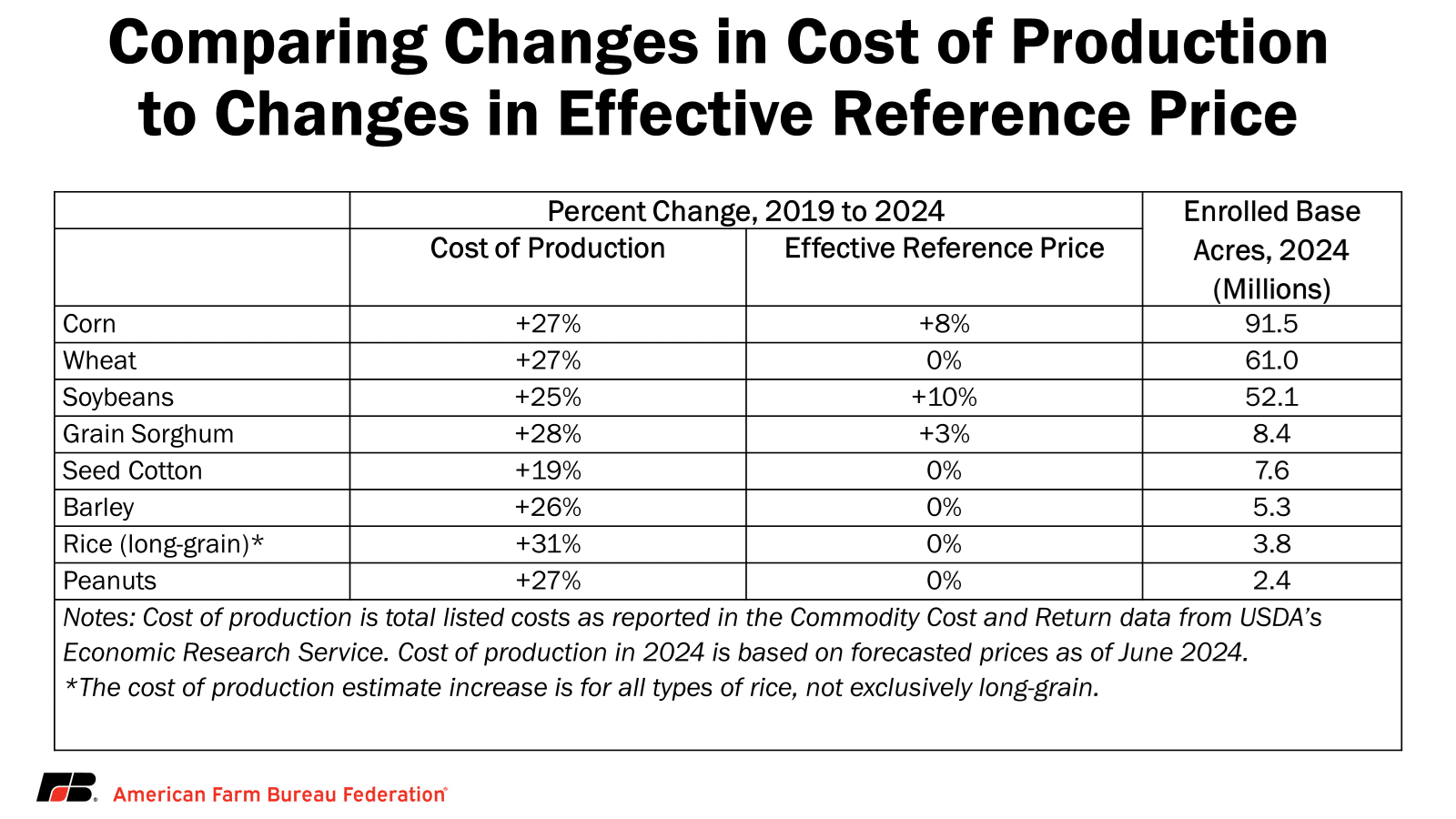

This graphic from the American Farm Bureau Federation paints a clear picture of the discrepancy between current costs of production and the outdated reference prices per crop:

An additional one-year extension of the 2018 farm bill would continue to include out-of-date reference prices for crops and marginal support for dairy farmers, made even less effective due to inflation. Additionally, research funding would be stagnant and billions of dollars of conservation funding would be lost.

Helping farmers get through tough periods like the past several years with commodity programs and crop insurance helps maintain agricultural production capacity while also guaranteeing a steady supply of food for the nation and the world and the survival of farms and the communities they support economically.

Okay, but how does this impact hunger-relief organizations like Food Bank of the Rockies?

Sarah Mason with Feeding Colorado, which advocates for all five Feeding America food banks in Colorado as well as Food Bank of Wyoming, explained that in recent years, food banks have seen more people needing food assistance, especially in the last two years as pandemic-era SNAP benefits ended and grocery prices have risen sharply.

“The biggest impact of a delayed farm bill is that we’re not going to be able to make progress on that increased need that we’re seeing in communities. We’re operating in a very different environment right now than we were six years ago,” Mason said in a recent interview.

The clearest example of this can be seen with the reduction of TEFAP support. This federal program has historically provided a large amount of food for food banks, and when that food support decreases, organizations like Food Bank of Wyoming have to directly purchase that food to keep up with demand.

Food Bank of Wyoming Executive Director Jill Stillwagon put it this way: “Historically, the Food Bank purchased about 10% of its food supply. In the last few years, that portion has tripled.”

In addition to the decline in federal food support through TEFAP, right now the rates of food insecurity in Wyoming and the U.S. are higher than they have been in a decade. According to the most recent USDA Household Food Security in the United States study, in 2023, 58% percent of food-insecure households participated in one or more of the three largest federal nutrition assistance programs: SNAP, WIC (the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) and the National School Lunch Program.

The study also revealed that last year, 13.5% (18 million) households experienced food insecurity, meaning that at some point during the year, the household had difficulty providing enough food for all their members because of a lack of resources. The 2023 prevalence of food insecurity was statistically significantly higher than the 12.8% recorded in 2022 (17 million households), 10.2% in 2021 (13.5 million households), and the 10.5% percent in 2020 (13.8 million households).